These days it’s common to talk about closing the “achievement gap,” significant and persistent disparities in academic performance between groups of children. The concept of an achievement gap dates back to the 1960s and focuses on the differences in educational outcomes by race (between white children and children of color) and socioeconomic status (between children from low-income and higher income households). But when we look beneath the surface, a more nuanced picture emerges.

These days it’s common to talk about closing the “achievement gap,” significant and persistent disparities in academic performance between groups of children. The concept of an achievement gap dates back to the 1960s and focuses on the differences in educational outcomes by race (between white children and children of color) and socioeconomic status (between children from low-income and higher income households). But when we look beneath the surface, a more nuanced picture emerges.

In Dalton Conley’s 1999 book Being Black, Living in the Red, he showed that the black-white achievement gap disappears when we control for wealth (not income). And more recently, in his 2008 book Outliers: The Story of Success, Malcolm Gladwell uses longitudinal reading scores from Kindergarten to fourth grade in Baltimore Public Schools to show that low, middle and high-income children all gain academically during the school year. It’s the summer months where the achievement gap occurs.

Focusing on just the summers, Gladwell shows that low-income children experience a net loss when we add up the four summers following first grade through fourth grade. By contrast middle and high-income children continue to gain in reading over the summer. Compared to low income kids, by the start of fifth grade, middle income kids’ cumulative reading gains are 27 times higher and high-income kids’ cumulative reading gains are 202 times higher. In the mid-1990s, Harris Cooper, a professor at the University of Missouri, published a meta-study which found on average students lose about a month’s worth of learning over the summer. And the losses are even greater among children in low-income households. According to the National Summer Learning Association, summer learning loss during elementary school accounts for two-thirds of the achievement gap in reading between low-income children and their middle-income peers by ninth grade.

Why does this happen? According to the NSLA, nearly half of parents have never heard of summer learning loss. They don’t know that their children experience a “summer slide” if their brains are not stimulated over the summer months. And they don’t know that teachers spend the first several weeks of school re-teaching material from the previous school year. But this doesn’t mean that parents don’t care.

In spring 2016, Read Charlotte along with many community partners surveyed 621 families of elementary school aged children (K-5) to find out their preferences for the summer months. Majorities of both low-income (69%) and higher income (73%) families reported that they want their children to keep reading over the summer months. Similar percentages want their children to experience new things. And about two-thirds of families across income levels want their children to attend summer camp.

But the reality is that not all children have the same opportunities for summer learning.

Malcolm Gladwell argues that “virtually all of the advantage that wealthy students have over poor students is the result of differences in the way privileged kids learn while they are not in school.” It’s easy to find evidence for Gladwell’s point when we review the cost of summer learning opportunities here in Charlotte-Mecklenburg. In Summer 2018, it will cost a family about $1,500 to $2,100 to send one child to five weeks of traditional summer camp filled with science, crafts and sports at places like Discovery Place, UNC Charlotte, or the YMCA. (This is on track with the national average weekly cost of $288 a week for summer camps.) Unfortunately, these types of opportunities are financially out of reach for a family of four with annual income below the 2018 federal poverty guidelines of $25,100.

The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Opportunity Task Force highlighted early care and education as a key factor in giving every child a fair chance to be successful in life. But education isn’t bracketed between the months of August and May; it happens all year round. Right now, some kids get more of an opportunity to keep learning while others stagnate or even fall behind during the summer months.

The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Opportunity Task Force highlighted early care and education as a key factor in giving every child a fair chance to be successful in life. But education isn’t bracketed between the months of August and May; it happens all year round. Right now, some kids get more of an opportunity to keep learning while others stagnate or even fall behind during the summer months.

Fortunately, there is something we can do about it.

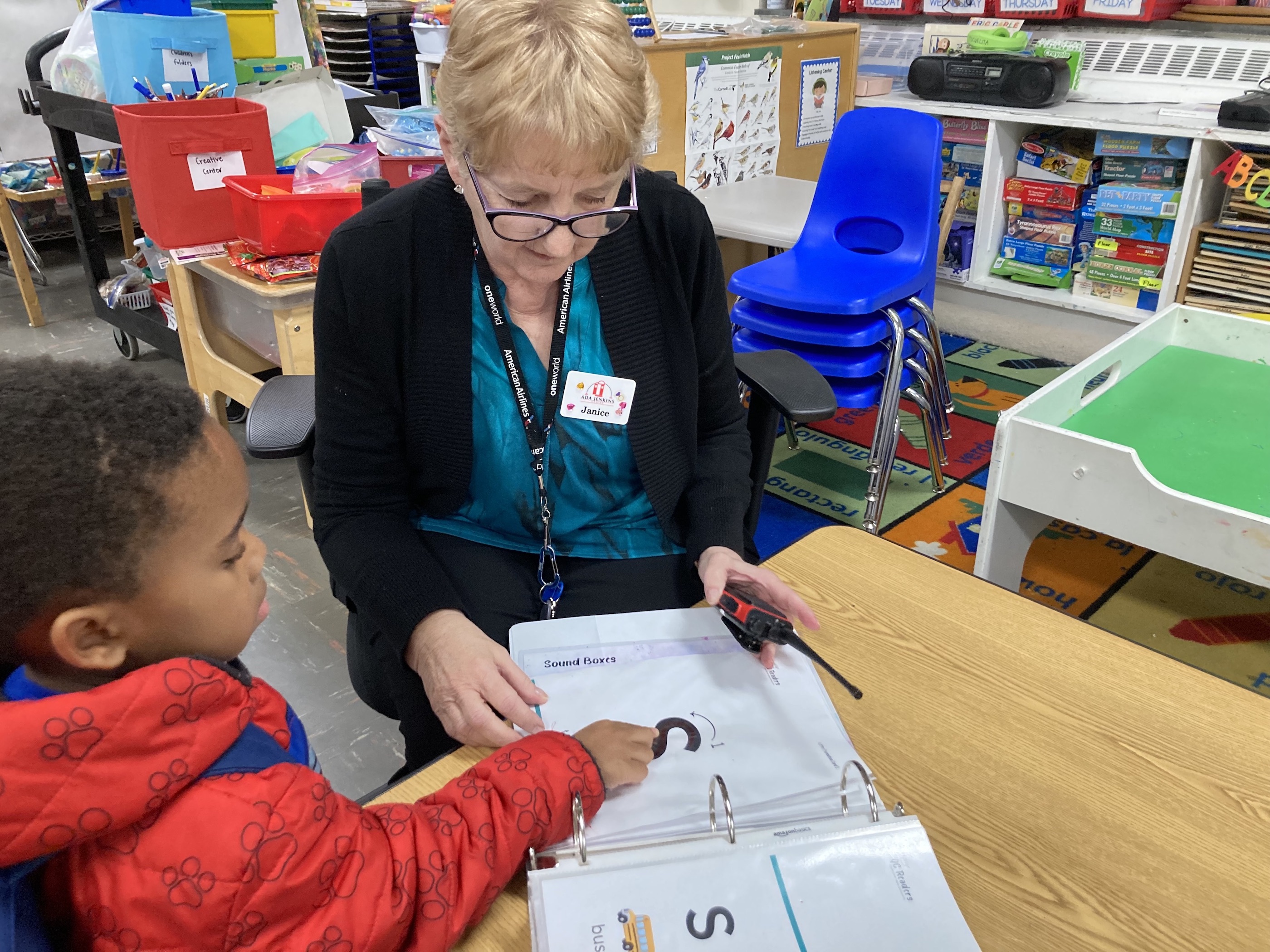

- We can make sure parents/caregivers know how important it is to keep their children reading and learning over the summer months. Studies of children’s motivation to read shows that before 3rd and 4th grade children are especially motivated to read to please the adults in their lives. Letting children know you want them to read—and talking with them about what they read – is an incredibly powerful incentive for summer reading. Making time to read with kids also helps. Spending as little as 15 minutes three times a week is a proven way to build children’s language, vocabulary and comprehension.

- We can make sure kids have access to books. Research shows that reading as few as 4-5 books over the summer can help maintain kids’ reading levels. But don’t just throw books at them. Helping kids find books that match their interests and reading level is important to making sure the books are read. Both “tree books” and e-books are solid options. The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools allows kids to access its online reading materials like Raz-Kids. The Charlotte Mecklenburg Library has a huge Pre-K through 4th grade e-book collection available for access online (kids can use their student ID number through the ONE Access program). While you’re at it, consider participating in the Charlotte Mecklenburg Library’s Summer Break program for ideas on how to keep kids’ reading, learning and thinking over the summer months.

- We can help more folks learn about the number of local nonprofits offering free summer programs for children and families that can’t afford the hefty price tag of summer camps. Many of these programs combine a focus on academics (including reading) with enrichment opportunities to keep summer learning fun. Community groups like the YMCA, YWCA, Above and Beyond Students, BELL, Freedom School Partners, and International House offer summer programs that keep children learning.

This summer, let’s work together to help tackle some of these challenges. Let’s spread the word that learning happens all year long, that there are things families can do to encourage reading at home, and there are community groups working hard to make sure every child has access to books. #SummerReadingCLT