By Munro Richardson

After I joined Read Charlotte in 2015, I began a multi-year deep dive into reading research in order to develop a panoramic view of what’s known (and not known) about how to improve early literacy outcomes. In Summer 2017, I began to follow the remarkable research of Dr. Carol Connor and her colleagues. While other academics rightly focused on unpacking how children learn to read, these researchers zeroed in on the dynamics of how to teach children to read.

Over a 20-year period, this group of researchers conducted multiple experimental studies, the results of which were published in more than 30 peer-reviewed journal articles. Along the way, they made a number of important discoveries about effective reading instruction. The insights from this body of research today informs Read Charlotte’s work across our three focus areas: PreK-3 classroom instruction, high-impact tutoring, and family empowerment. We’re helping our community partners to leverage this evidence-based knowledge in their work with children and families.

Here are ten powerful, evidence-based drivers of effective reading instruction for PreK-3 students. (Click here for a summary of the research studies associated with each of these drivers.)

Driver 1: Provide appropriate amounts of the Four Types of Reading Instruction. Some reading instruction teaches “code-focused skills” and some reading instruction teaches “meaning-focused skills.” Code-focused skills include letter knowledge, phonemic awareness, phonics, spelling, and fluency. Meaning-focused skills include vocabulary, comprehension, and writing. Children need to master all of these skills to become skilled readers.

There are two ways this instruction can be delivered – teacher-managed or child-managed. “Managed” refers to who is directing the learner’s attention – the teacher or the child. Child-managed includes individual and peer work. Who’s managing the learning matters in different ways at different times. Together these two sets of skills and two modalities of instruction produce the Four Types of Reading Instruction.

The Four Types of Reading Instruction interact with each other. All children need all Four Types – but need different amounts (daily minutes) and ratios of the Four Types at different times. This is because these Four Types also interact with children’s reading skills – word reading, vocabulary, and comprehension. The amounts of the Four Types of Reading Instruction, and the level of instructional difficulty needed for each child to increase reading mastery, varies by child and changes over time.

Seven experimental studies repeatedly demonstrated the validity of this major driver across grade levels and different curricula and instructional resources. At Read Charlotte, we view the Four Types of Reading Instruction as a key framework for improving PreK-3 reading outcomes.

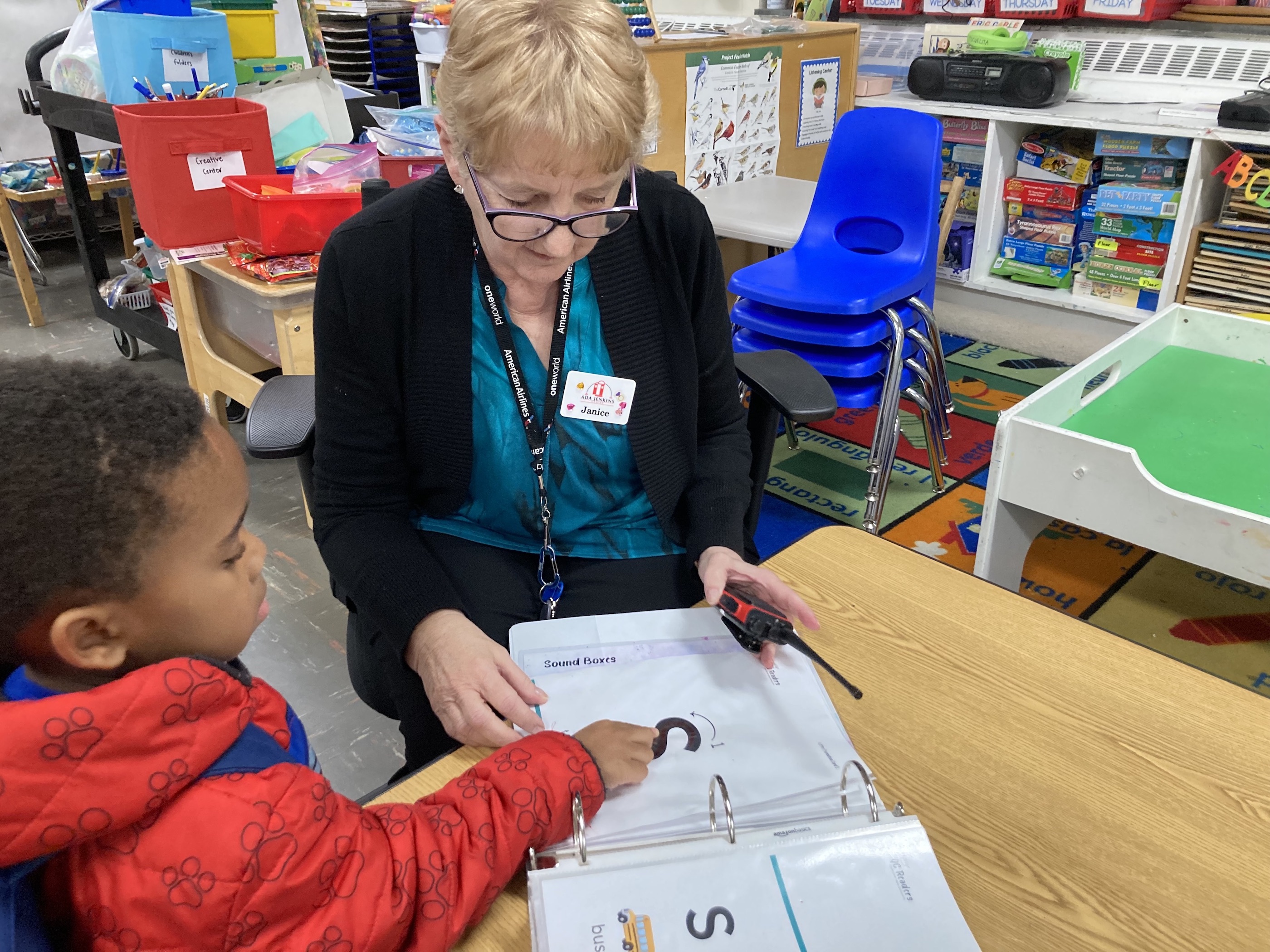

Driver 2: Maximize the benefits of small-group instruction. Teacher-managed small group reading instruction is four to ten times more effective than whole group instruction. The biggest impact occurs in PreK and kindergarten, where it’s ten times more effective than whole group instruction. Small groups are important for both code- and meaning-focused instruction. Small groups organized by student needs for both code- and meaning-focused instruction allows educators to more closely individualize instruction. Helping educators run smart, effective small groups (see Driver 7) will turbocharge efforts in the classroom and in out-of-school settings.

Driver 3: Optimize code-focused instruction. Educators are rightly paying more attention to ensuring children develop foundational literacy skills. However, Dr. Connor and her colleagues found it’s important to get students the right amounts (and proportions) of code-focused instruction. Too much or too little code-focused instruction can lead to weaker gains. (I think this is an example of the Goldilocks principle.) To hear Dr. Connor speak on this point, click here and go to the three-minute mark. Other researchers also agree with this.

Driver 4: Provide plenty of meaning-focused instruction. In contrast to code-focused instruction, there is no apparent Goldilocks principle for meaning-focused instruction. Dr. Connor and her colleagues found that when it comes to building children’s vocabulary, writing, and comprehension skills there is no such thing as “too much” as long as we also provide sufficient code-focused instruction.

Driver 5: Optimize child-managed instruction. Children who are on grade-level or advanced in reading generally need more child-managed instructional time, however, many of our core curricula and interventions are heavy on adult-managed instructional activities. While this is appropriate for children who are behind in reading, it misses what students at grade-level or advanced readers need to maximize their reading growth. Furthermore, all students typically need increasingly more child-managed instruction as the school year progresses. Optimizing child-managed instruction helps to ensure we do not unwittingly place artificial limits on children’s reading growth by failing to provide sufficient child-managed instructional time.

Driver 6: Support strong teacher literacy knowledge and pair it with explicit literacy instruction. Teacher knowledge and literacy instruction work together. Building teacher literacy knowledge on its own does not automatically lead to student reading gains. It’s the combination of teacher knowledge and explicit instruction together that produces improvement in children’s reading. One without the other doesn’t work. But this interaction can also work in reverse. Low literacy knowledge with high levels of explicit instruction can lead to weaker and possibly negative gains in reading. A highly scripted curriculum cannot make up for shortcomings in either area.

Driver 7: Create a strong learning environment. Another important interaction occurs between the classroom learning environment and reading instruction. Classroom environment and reading instruction work together. A classroom using the Four Types of Reading Instruction (Driver 1) with good small groups (Driver 2) will outperform a classroom not using this approach to individualize reading instruction. But a classroom using Drivers 1 and 2 with a strong learning environment – classroom organization, teacher responsiveness, and support for vocabulary development – will produce even better reading outcomes.

Driver 8: Intervene with struggling readers sooner. When an assessment or screener shows that a student is behind in reading, sometimes the response will be to see if the student is able to catch up with core instruction (Tier 1). If a student doesn’t improve, then they are given extra intervention (Tier 2 or 3). It turns out that the timing of intervention matters. Providing reading interventions as soon as children show they need help leads to greater improvement in outcomes than waiting to see if they improve from core instruction. The timeliness of intervention provides its own benefit.

Driver 9: Neutralize growth-limiting beliefs. Teachers’ subjective beliefs about student abilities based upon non-academic factors such as school lunch status, behavior, and social skills can lead to reduced student reading (and math) performance. (I think this is an example of the Golem effect.) These growth-limiting beliefs, however, can be neutralized by providing teachers with timely, objective information about students’ actual abilities and instructional needs.

Driver 10: Provide early and continued individualized reading instruction. It’s not enough to provide good individualized reading instruction for one or two years and then stop. A multi-year experimental study of children from first through third grade found no “inoculation” for students who received good individualized instruction in first grade but “regular instruction” in second and third grade. Children ideally need small group-centered reading instruction, informed by the Four Types of Reading Instruction, for the first five years of schooling (PreK-3) to reach their full potential by third grade.

Today, we are translating these insights into early literacy work in the community. It’s important to note that these ten drivers are evidence-based practices – not programs. Practices can be more readily integrated by organizations into existing strategies and programs. Click here to read more about our work.