What Works

Determining “What Works”

The Read Charlotte team put in over 1,000 hours of review over two-dozen databases and clearinghouses that catalogue “what works” for a variety of education and social programs. We used a fairly conservative approach to identify “what works.” As much as possible we rely upon third-party review of the quality of the research. In the coming weeks, we will begin to share evidence-based interventions (curricula, programs, software, etc.) we have found that align with our community indicators and five buckets. We are guided by an initial set of criteria to determine which interventions to recommend to the local community for consideration:Does this intervention have evidence that it can move the needle one or more community indicators?How strong is the evidence for this specific intervention?Does the projected size of the impact of this intervention meet or exceed what we would normally expect to see for a given outcome?What is the likely cost-benefit calculation for this intervention?What are the risks of “execution failure”?

Evidence-Based Interventions

In order to tell what works, we look for strong “cause and effect” relationships between specific interventions and particular outcomes. For example, does a specific tutoring program improve outcomes for a particular reading skill? In order to draw a valid conclusion, we need to be able to rule out alternative explanations for the results. For example, what if there is something different about the students who participate in the program compared to other students? What if the school introduced a new curriculum that is influencing the results?The only way reliably to determine cause and effect is to compare outcomes between two different groups. We cannot determine whether a program “works” unless we can compare it to an alternative practice. Think of this as an experiment, where one group that is exposed to the program (the “treatment”) and the other does not get the program (the “control”). The impact of an intervention is the difference in the average results between the treatment and control groups. Many programs don’t have this level of evaluation and so we can’t answer the question whether “it works.”An alternative, however, is to draw a strong association between specific outcomes and program participation. Such an approach could combine data from a pre-test and post-test with other information about program participants (e.g. grade level, age, gender, race, etc.) to try to “control” for differences between program participants. This approach would allow us to measure the correlation between program and outcomes. The caveat of course is that correlation is not causation.

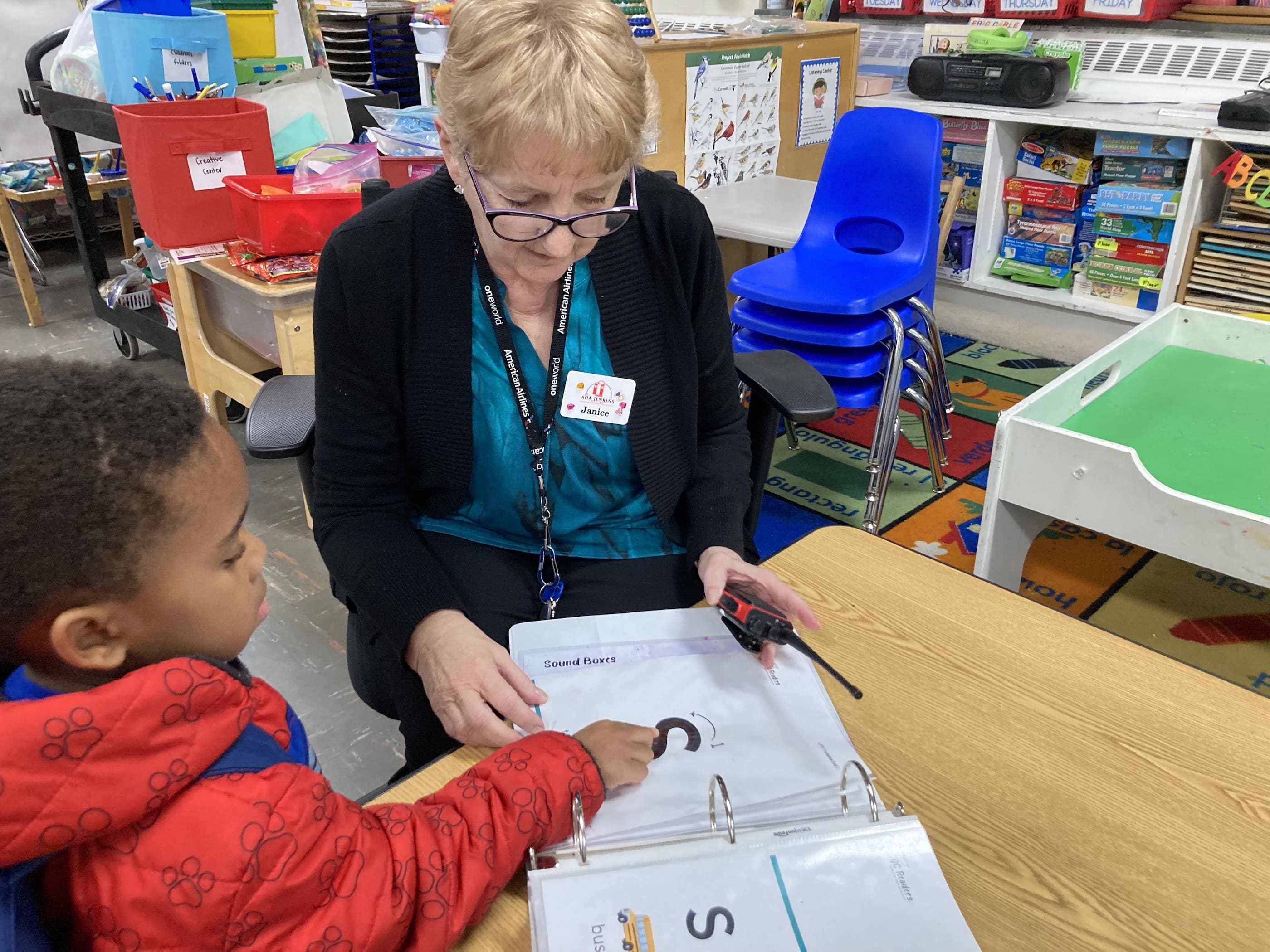

A Focus on Practices and Programs

We looked for evidence-based practices and program models that have been rigorously tested on whether they can move one or more of our community indicators. A practice is a general category of strategies or procedures that can be used in a variety of contexts (home, classroom, out of school) guided by specific principles but often flexible in how it is carried out. An existing organization can incorporate evidence-based practices within its current programmatic offering. A program, however, has specified goals, objectives, and structured components (e.g., a defined curriculum, an explicit number of treatment or service hours, and an optimal length of treatment) to ensure the program is implemented with fidelity to its model.For example, peer tutoring is a practice that involves having students coach one another with defined roles and a focus on task completion. PALS (Peer Assisted Learning Strategies) is a specific peer tutoring program developed by researchers at Vanderbilt University. There is research evidence for both peer tutoring as a general practice and PALS as a specific peer tutoring program.

Many Studies are Methodologically Flawed

A common challenge we found in our review is that many studies suffer from serious methodological flaws. It’s not uncommon at all to see the What Works Clearinghouse review over 50 studies for a program and conclude almost all of them are too flawed to be included in the review. A common shortcoming is the failure to establish similarity between program participants that receive an intervention (the “treatment” group) and non-participants (the “control” group). Without clear information to prove the two groups are virtually the same we can’t rule out alternative explanations for program outcomes. Another common challenge is attrition—when program participants (and members of control groups) disappear from the study. Some attrition always occurs. But when too many people leave it’s hard to know whether the results truly represent what we can expect for the general population or not.

Many Interventions Have Weak to No Positive Effects

Since 2002 the Institute for Education Sciences (IES) within the U.S. Department of Education has commissioned many well-conducted randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the effectiveness of diverse educational programs, practices, and strategies (“interventions”). These interventions have included, for example, various educational curricula, teacher professional development programs, school choice programs, educational software, and data-driven school reform initiatives. A clear pattern of findings in these IES studies is that the large majority of interventions evaluated produced weak or no positive effects compared to usual school practices. Of the 90 IES-commissioned studies from 2002-2013, only 11 (12%) were found to produce positive effects. This pattern is consistent with findings in other fields where RCTs are frequently carried out, such as medicine and business,and underscores the value of rigorous evaluation to know what works for education.