A look at Year One in Charlotte and its game-changing potential in Read Charlotte’s community-wide initiative to double literacy rates

By Liz Rothaus Bertrand

When Munro Richardson first heard about the HELPS Program from a colleague in the United Way of the Greater Triangle, he was skeptical. Richardson, Executive Director of Read Charlotte, and his team had spent a year conducting a massive survey of literacy interventions tied to the critical skills and competencies that kids need to master in order to succeed in third grade: HELPS (which stands for Helping Early Literacy with Practice Strategies) hadn’t shown up anywhere on it.

But his curiosity was piqued. The evidence-based, research-validated tutoring program, developed by NC State Professor John Begeny, was reporting better than average results in multiple studies. Whereas most literacy interventions lead to improved outcomes for an average of 3 – 14 students out of 100, HELPS was showing added progress in an average of 35 students per 100.

Richardson decided to look more closely at the program and test it locally. “I really felt like HELPS was this hidden gem in our backyard that I was fortunate someone told us about,” says Richardson.

The HELPS Program focuses on reading fluency: that’s the ability to read with speed, accuracy, and proper expression. “Fluency is often referred to as the forgotten literacy skill,” says Richardson. “…It’s the bridge between sounding out words and comprehension.”

If you have ever studied a foreign language, learned how to pronounce individual words, and read a page of text too slowly and with too much effort to easily comprehend what you are reading—you can understand the importance of reading fluency. The HELPS Program targets this skill, through 1:1 tutoring.

Read Charlotte estimates about 20%-25% of third graders in Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools (CMS) learn to sound out individual words (phonics) but don’t read with enough speed or accuracy (fluency) to fully understand what they are reading. Richardson believes many of these students could achieve at College and Career Ready levels on state end of grade (EOG) exams if effective interventions are put in place early enough. Research finds high correlations between reading fluency, comprehension and overall reading achievement.

As Read Charlotte studied HELPS and started conversations with CMS about it, Richardson grew increasingly confident that this intervention could be a powerful tool in improving literacy but only if it could be implemented well.

He recruited three local groups to participate in training and implementation at their summer camps in 2018. Some sites, like UNC Charlotte’s summer reading camp, included experienced tutors. But others like Urban Promise—a program that enlists high school students as mentors for younger kids—had enthusiastic newcomers.

Could both kinds of tutors make it work?

“When I saw that high school students could do it, I knew we could do it here in Mecklenburg County,” says Richardson.

Results of Year One in Charlotte

Fast forward a year and it’s obvious Richardson’s confidence in HELPS was well placed. With the help of dozens of community partners and individual volunteers, the program piloted in 10 Charlotte-Mecklenburg elementary schools during the 2018-19 academic year with impressive results:

● The average CMS third grader who received HELPS 1:1 tutoring started in Fall 2018 reading 51 words correct per minute (WCPM)—a full year behind in reading fluency.

● At the end of the school year, 46% of the third grade students who received HELPS 1:1 tutoring exceeded national norms for expected growth in oral reading fluency.

● Students who received the most HELPS tutoring sessions showed the most growth:

-Those who received 30 or more sessions closed 57% of the gap needed to get to 100 WCPM, the benchmark for on-level reading fluency at the end of third grade.

-Those who received 40 or more sessions closed 63% of the gap needed to get to 100 WCPM by the end of third grade.

-Those who received 50 or more sessions closed 75% of the gap needed to get to 100 WCPM by the end of third grade. This is a gain of slightly more than 1½ grade levels.

These promising results happened in spite of two fall hurricanes, which closed schools for 5 days, and staggered HELPS Program start dates for participating schools—ranging from September to January.

How We Know HELPS Works

Educational equity drives the work of Begeny, who began developing and testing content for the HELPS Program back in 2005. Early in his career, he recognized the importance of reading fluency as a key component in literacy. His goal was to integrate the strategies into a package that could easily be used by educators. In 2010, he started the non-profit Helps Education Fund to make this intervention, and others supporting educators in critical areas, freely available.

Since its inception, several research studies have evidenced the HELPS Program’s effectiveness. Over the years, Begeny and his team have also heard from hundreds of educators who have implemented the program and seen it work with their students.

“[T]hat to me is equally important,” says Begeny. “Educators develop a lot of experiential knowledge. When you hear that enough it certainly adds to what we’re seeing in the research.”

Read Charlotte’s pilot year, the largest known project to systematically evaluate HELPS in a single year, also helped answer new questions about the program in a real world setting. In particular, what would happen if the program were implemented by hundreds of volunteer tutors? Could it be effective?

The answer was a resounding yes.

“We were getting a lot of positive feedback from tutors and teachers…” says Begeny. “But the end of year data really helped to solidify that, on average, the students receiving HELPS made reading improvements beyond what we would expect from national data. Also, we found that the students who received the most HELPS sessions made the most progress.”

A Local Educator’s Perspective

Tammie Holt, Executive Coordinator for CMS’s Central 1 Learning Community, played a key role in launching and supporting the HELPS Program at five different schools last year. While she saw plenty of anecdotal evidence that the tutoring method was helping students, she says the first year of results confirm those suspicions.

“[T]o have these concrete data that support our observations, even surpassing our expectations based on the research, has been extremely powerful,” says Holt. “It also helps us tell the story of HELPS, no longer from a hypothetical lens in Charlotte, but from a place of tangible results.

“HELPS tutoring really embodies the definition of impactful partnerships in education. Schools, community members, and educationally focused organizations get to work together towards an important and common goal—increasing students’ fluency in order to grow better readers in Charlotte.”

At the Heart of It All: Collaboration

Like all of Read Charlotte’s initiatives, the HELPS Program depends on the efforts of community partners. Many groups and individuals leaned in and invested in making this a successful pilot year. “These results didn’t happen by accident,” says Richardson. “It was a lot of careful coordination and communication between community groups.”

A core group of organizations assisted with the launch and implementation: Helps Education Fund, Augustine Literacy Project, United Way of Central Carolinas, Project LIFT and Read Charlotte. Other organizations partnered with Read Charlotte to assist with tutor recruitment and training. They ranged from groups as varied as the American Girl Store and Black Child Development Institute to Temple Beth El and YMCA of Greater Charlotte.

“You saw organizations looking past their own programs and not necessarily trying to get credit but rolling up their sleeves and helping where they could,” says Richardson.

This focus on collaboration is something that has impressed HELPS lead developer Begeny as well. “To my knowledge, the work led by Read Charlotte last year was the largest effort within a city or school district to build capacity of HELPS implementation by involving community volunteers,” he says. “Read Charlotte clearly recognizes the value of partnerships in working toward shared goals around literacy. In my opinion, they have thus far been superb with facilitating community-wide collaboration across many CMS schools and local partnering organizations.”

To do this well, it takes careful planning that allows for capacity building, impact evaluation, and consideration of critical aspects of sustainability. Program fidelity is also essential, says Begeny, noting that Read Charlotte recognizes both the importance of tutors implementing the program as designed as well as the need for every participating student to get a certain number of HELPS sessions.

A Volunteer’s Perspective

When Carla Walden relocated to the Queen City after a 38-year teaching career in California, the last thing she planned to do was get involved with a school. “I got here to Charlotte and really didn’t want to do anything with children at all. I just really needed a break,” says Walden, who moved to make her retirement pension stretch further. But after a winter visit from her grandchildren, she realized she missed being around kids and started looking for volunteer opportunities.

She knew from educational research and her own experience how important it is for kids to be reading on grade level by third grade. “That’s still the pivotal time when you’re learning to read… this program struck me because it aligned with what I knew was true: you have to get the children’s reading fluency up.”

It was easy to register online, submit her info for the required background check, and then choose a 3-hour training session at a time that suited her schedule.

“Everything aligned itself really well,” says Walden. “[I] went to the training and it confirmed to me that everything was research-based… the training was rigorous and on point.” After her initial training, coaches continued to provide additional guidance on implementing the highly-scripted program. The students, who had started tutoring sessions earlier in the school year with other volunteer tutors, also seemed to enjoy helping her learn the routine.

“It was really boosting their self-esteem knowing they were helping me learn the program,” says Walden, who tutored at Winterfield Elementary School, close to where she lives.

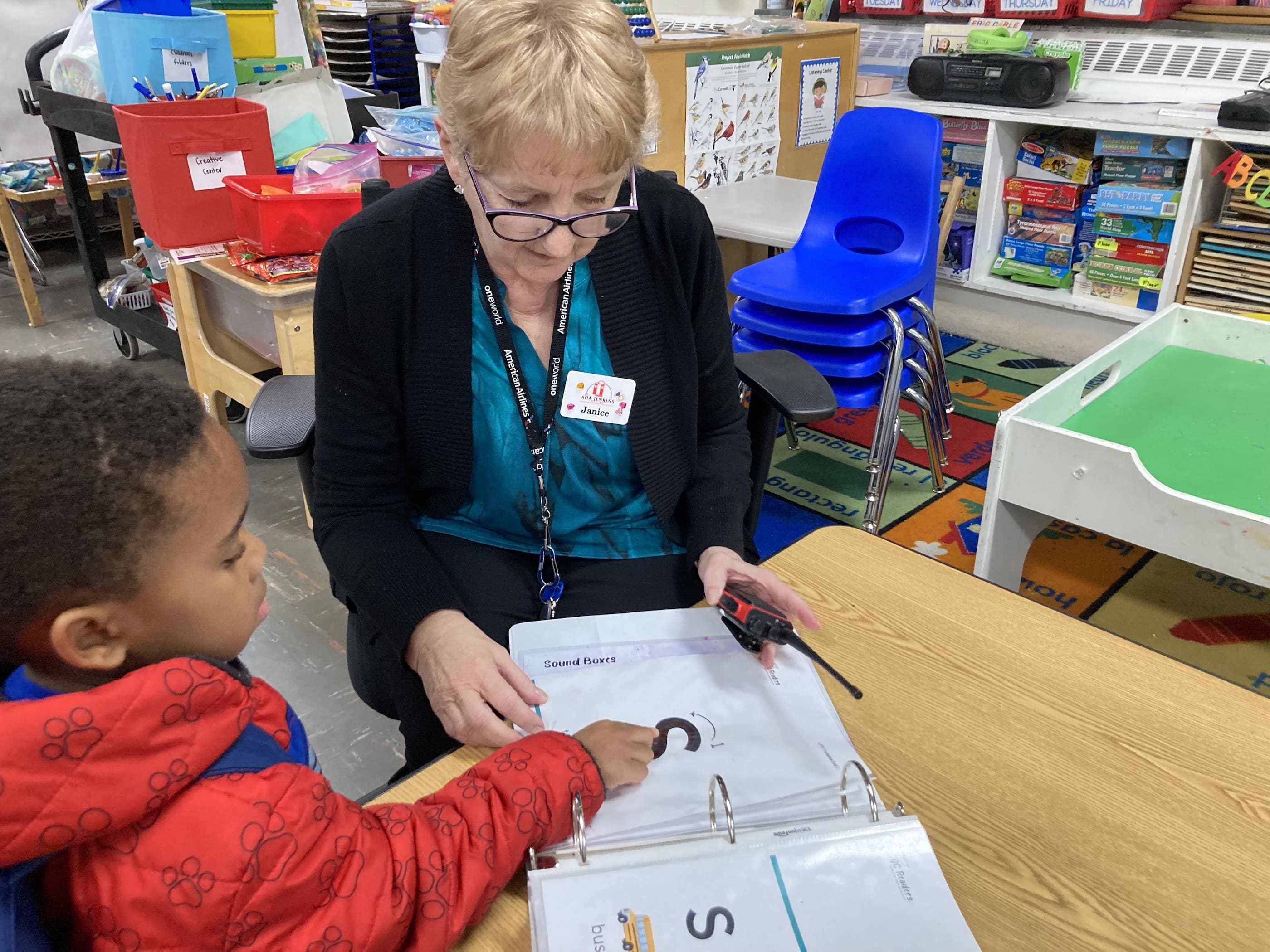

Every 15-20 minute HELPS tutoring session includes a timed reading of a short text, modeling, corrections and a reward system encouraging progress. Tutors track progress and share this information with students at every session.

“What I like is it’s targeted, it’s specific and it’s something where children can say I know I’m doing better,” says Walden. “… It really excited them to see they were making progress from one session to another.”

Walden, who has low vision, no longer drives. She booked a Lyft service every Friday from the retirement community where she now lives so she could make her weekly tutoring sessions.

“[The HELPS program] was so well organized that we knew we were making a difference,” says Walden. “Being retired, I could be spending my time doing a whole lot of other volunteer work in the city. There are so many other needs. But my experience made me want to focus most of my volunteer efforts in the Charlotte-Mecklenburg school district.”

Next year she will be splitting her volunteer time between three schools, supporting HELPS as well as the Heart Math Tutoring program. She’s not alone. As of August, 224 tutors are signed on for the second year of HELPS tutoring.

Expanding a Model that Works

HELPS has the potential to make an even bigger difference but it depends on people and community partnerships to power it. Richardson says colleagues in Guilford and Durham Counties are looking at what has happened in Charlotte with HELPS and how they can implement it in their communities too. Charlotte serves as an outstanding example of what is possible when community volunteers, community organizations, businesses and faith communities come together in a coordinated way and begin to move the needle on literacy.

“I couldn’t be prouder of this larger community effort and I’m excited about how we can grow that further,” says Richardson.

During its pilot year, Read Charlotte intended for every student to have three HELPS tutoring sessions per week but that wasn’t possible at every school. “Our major barrier this year was simply not having enough volunteers [to make it happen],” says Richardson.

Increasing volunteer numbers is even more crucial now since Read Charlotte aims to approximately double the number of students receiving HELPS tutoring next year by expanding into second grade classes at most participating schools.

Targeted tutoring like HELPS is just one part of Read Charlotte’s overall strategy to improve literacy. Other essential components include building home libraries, providing resources to encourage literacy at home, supporting quality teaching and stopping summer reading loss.

“When you start to stack and align it, it becomes really powerful…” says Richardson. “It becomes a powerful tapestry that you knit together.”

Real, sustainable change comes from addressing challenges head on with research-based solutions. As Read Charlotte works to improve systems, more than ever it needs the concerted effort of many people coming together.

“To help address the many educational inequities that exist today, we need all hands on deck,” says Begeny. “There’s no one program or one initiative that’s going to fix it all. To address our biggest societal challenges and needs—within education or otherwise—we need community members, diverse leadership, and multiple organizations to authentically collaborate.”

Get Involved!

While the goal is to get as many HELPS tutors signed up early in the school year in order to give students the most possible sessions, tutor trainings are scheduled through the end of January 2020 and volunteers may continue to sign up over the next several months. Become a HELPS volunteer today or support efforts to transform literacy in Charlotte-Mecklenburg in other important ways.